Being a caregiver in a military family is akin to participating in an intricate dance. We traverse the battlefield of emotions, the trauma minefields, and the vast healthcare terrain, all while guiding our service members towards recovery.

This journey demands resilience, love, and infinite patience, often accompanied by the silent struggles of mental health and the risk of suicide ideation.

As a military spouse and caregiver, I’ve walked this challenging path, supporting my husband, a proud combat infantryman, through deployments, injuries, and the emotional aftermath of their service. But beneath this journey lies a concealed aspect, shrouded in silence, stigma, and shame: the cycle of violence and abuse that some military caregivers, like me, have experienced.

This cycle, rarely acknowledged or discussed, is the focus of this article.

Understanding the Cycle of Violence in Military Caregiving

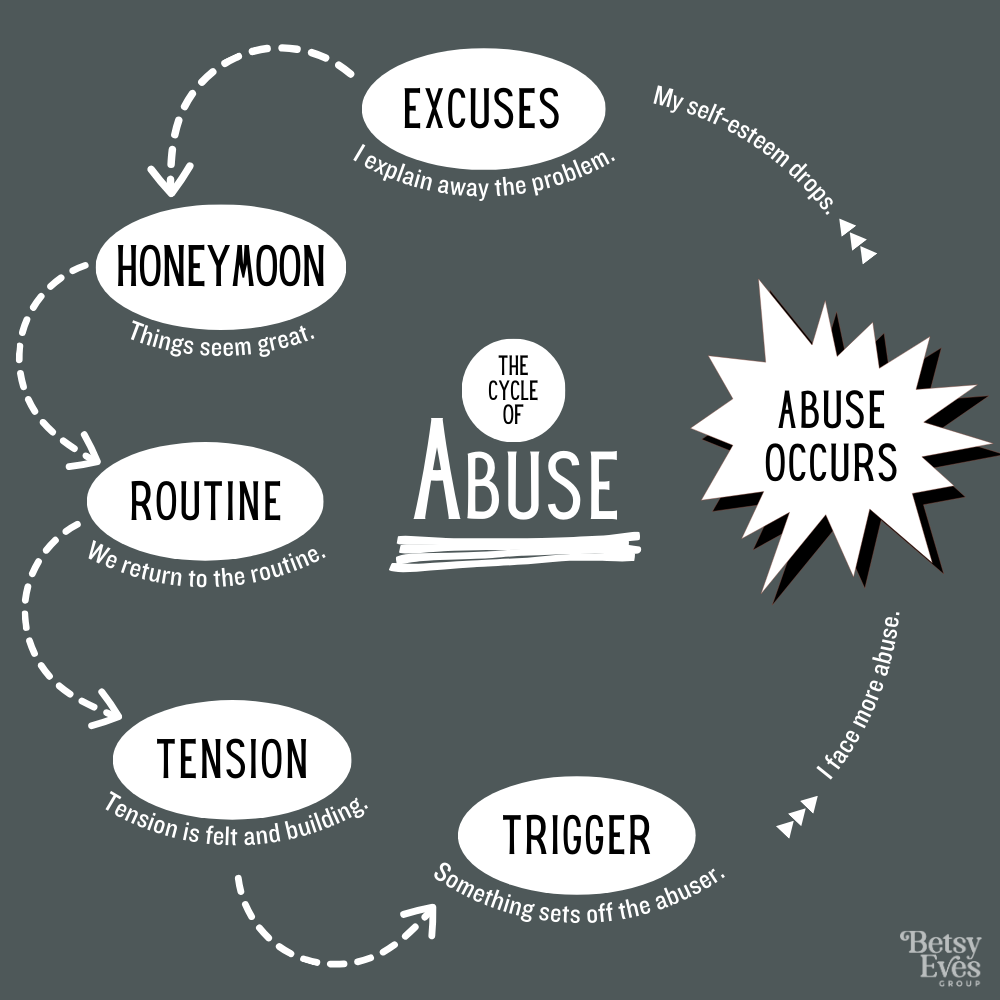

The cycle of violence is a framework crafted to interpret the intricate and nuanced relationship between abusive and loving behaviors.

It’s a tool for those unfamiliar with domestic violence and abuse, illustrating why breaking free is more than just “leaving.”

This cycle comprises three phases:

Tension-Building Phase: Tensions rise, often beginning with minor disputes. It’s akin to navigating a minefield, where every step requires caution. According to research (Rentz et al., 2006), the tension-building phase is marked by escalating conflicts, a common precursor to domestic violence. As caregivers, we may find ourselves tiptoeing around potential triggers, desperately trying to prevent emotional explosions. It’s like watching the pressure gauge of a volatile situation, never knowing when it might reach its limit.

Acute or Crisis Phase: The storm unleashes. It can manifest as verbal, emotional, or physical abuse. Studies (Rabenhorst et al., 2014) have indicated a link between combat-related deployments and an increased risk of spouse abuse during the acute phase. This phase can be emotionally turbulent, much like trying to calm someone engulfed in anger and despair while ensuring their safety and your own. For caregivers, this phase is daunting. We’re not merely confronting an abusive partner but a service member battling trauma, anxiety, depression, or even suicidal thoughts.

Calm or Honeymoon Phase: Post-storm, a deceptive calm ensues. The abuser may express remorse or seek reconciliation. For military caregivers, this phase is perplexing. I’ve witnessed my service member’s vulnerability and remorse during this phase, underscoring its complexity, clinging to the hope that change is imminent. Yet, this hope is fragile, easily broken when the cycle restarts. It’s reminiscent of those moments when we see glimpses of the person we fell in love with, only to have that hope shattered by the recurrence of abuse.

As we unpack the harrowing cycle of violence and abuse, it’s imperative to pause and consider an aspect that often blurs the lines of understanding within military caregiving. This is the intersection where symptoms of trauma-related conditions, such as PTSD and TBI, can resemble, yet fundamentally differ from, patterns of abuse.

Recognizing these distinctions is vital for caregivers entrenched in the daily realities of supporting their service members.

Deciphering Shadows: Distinguishing PTSD and TBI from Abuse

In transitioning to this critical exploration, we must equip ourselves with the knowledge to discern the nuanced behaviors indicative of PTSD and TBI from those that are abusive.

This understanding is not just academic—it’s a lifeline for caregivers navigating the murky waters of care and compassion against the backdrop of potential abuse.

PTSD and TBI Explained

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition triggered by experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event. Symptoms can include flashbacks, severe anxiety, nightmares, and uncontrollable thoughts about the event (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), on the other hand, is a brain dysfunction caused by an outside force, usually a violent blow to the head. Implications of TBI can range from mild concussions to more severe brain damage, influencing behaviors and cognitive functions (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2020).

Behaviors Stemming from PTSD and TBI

Behaviors resulting from PTSD and TBI can sometimes mimic those seen in abusive relationships, which may include:

- Irritability or Angry Outbursts: Both PTSD and TBI can lead to sudden changes in mood, which can be misconstrued as abusive behavior (Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008).

- Withdrawal: Individuals may pull away from loved ones or avoid social interactions, which can be misinterpreted as emotional abuse or neglect (Hall, 2011).

- Confusion and Memory Issues: Particularly with TBI, individuals may struggle with memory and attention, potentially leading to misunderstandings and conflicts (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2020).

Abusive and Violent Behaviors

Conversely, abusive or violent behaviors are characterized by an intention to control, harm, or assert dominance over another person. These may include:

- Intentional Intimidation: Using threatening behavior to instill fear or compliance.

- Physical Harm: Deliberate use of force causing injury or pain.

- Emotional Manipulation: Purposefully exploiting emotions to control or degrade someone.

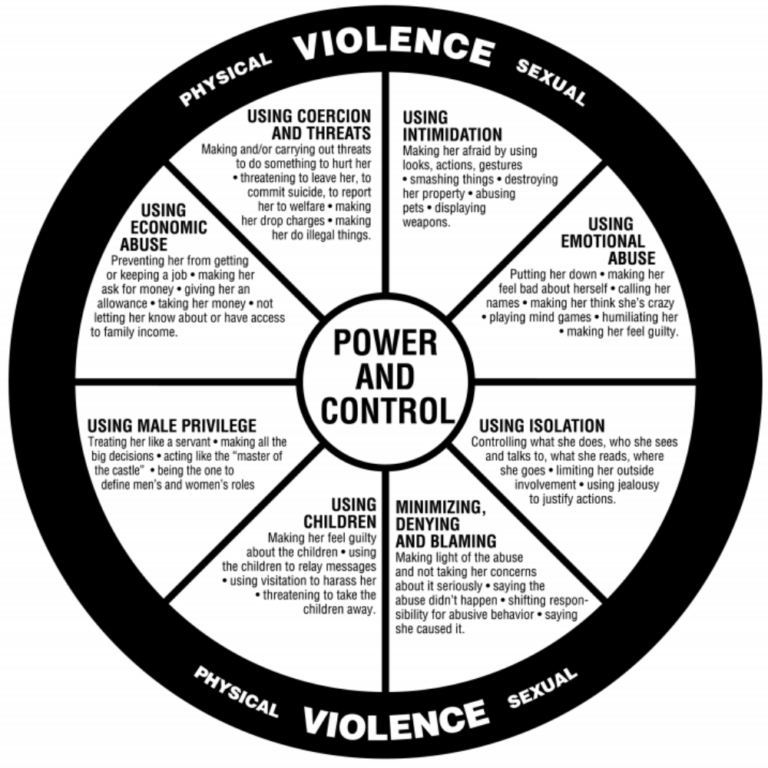

Power and Control Wheel

In the context of military caregiving, the Power and Control Wheel, developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, provides profound insight into the mechanics of abusive relationships.

While traditionally using she/her for survivors and he/him for abusers, it’s vital to acknowledge that abuse knows no gender or sexual orientation boundaries.

This tool illustrates how abusive partners exert dominance, employing a spectrum of tactics designed to entrap survivors within the relationship. At its core, the wheel encapsulates the insidious and ongoing behaviors—subtle yet pervasive—that underpin the abuser’s strategy.

Encircling these core manipulations is a ring of overt violence, both physical and sexual, that serves to fortify and intensify the grip of the more nuanced forms of control.

In military caregiving, recognizing these patterns is critical. The behaviors that fill the wheel’s spokes can often be mistaken for trauma-induced reactions, yet they are, in essence, deliberate actions aimed at maintaining power.

The outer ring’s blatant aggression echoes the crisis phase of the abuse cycle we’ve explored, reinforcing the urgent need for awareness and intervention in such dynamics.

Differentiating the Two

It’s crucial to understand that while PTSD and TBI can influence a person’s behavior, they do not inherently lead to abusive or violent actions.

Abusive behavior is a choice and is about power and control, not a direct result of trauma or injury (Hall, 2011).

Recognizing the Signs

To discern between the two, consider the following:

- Consistency and Context: PTSD and/or TBI-related behaviors often occur in response to specific triggers and are not consistently directed at a specific person with the intent to control or harm (Mobbs, 2020).

- Acknowledgment and Responsibility: Individuals with PTSD and/or TBI typically recognize and take responsibility for their behaviors, often feeling remorse, and seek help to manage their symptoms (Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008).

- Control and Intention: Abusive behavior is characterized by a pattern of controlling behavior and intent to manipulate or harm, regardless of remorse shown afterward (Rabenhorst et al., 2014).

Recognizing the crucial differences between the symptoms of PTSD, TBI, and abusive behavior not only enlightens us but also brings us to a pivotal juncture in our caregiving journey.

Armed with this knowledge, we find ourselves standing at the threshold of a profound dilemma that extends beyond medical diagnoses and into the realm of our daily interactions and personal relationships.

This brings us to the heart of the caregiver’s experience — a role steeped in empathy and loyalty, yet fraught with the complexities of love and duty in the shadow of potential abuse.

Seeking Help

If you’re uncertain about the behaviors you’re witnessing, seek professional advice. Mental health professionals can help differentiate between symptoms of PTSD, TBI, and abusive behavior. Moreover, they can provide tools for managing PTSD and TBI symptoms and guide you on how to respond to and address abusive behavior safely.

Understanding the challenges and fears that come with navigating difficult situations, this resource PDF has been created as a starting point.

Here, you’ll find contacts for those who can offer guidance and support, ready to point you in the right direction when you’re ready to ask for help.

Resource Guide: DOWNLOAD

The Dilemma of the Military Caregiver

Our primary role as caregivers is to support our service members. We stand by them through thick and thin, bearing witness to their battles: the sleepless nights, nightmares, overwhelming anxiety, and profound despair.

We recognize that their physical or emotional injuries aren’t their fault, and we laud their bravery for serving our country.

The Dual Role of Care and Victimhood

Yet, this intricate situation poses a dilemma that many military caregivers, including myself, grapple with while empathizing with our service member’s pain, we might also be victims of their abusive behavior.

In my own journey as a military spouse and caregiver, I’ve experienced the duality of this role. Supporting my husband through deployments and the challenges of post-war life has been a deeply rewarding experience, but it’s not without its complexities. I am both the support system and, at times, the unwilling victim.

“While empathizing with our service member’s pain,

Betsy Eves

we might also be victims of their abusive behavior.“

Navigating Emotional Cycles

There’s a striking parallel between the emotional cycle of deployment and the cycle of violence and abuse within military caregiving. Just as the emotional cycle of deployment has its “honeymoon” phase marked by joyous reunions, warm embraces, and a flurry of excitement, so too does the cycle of violence and abuse.

In deployment, this phase can also be a time of awkwardness and readjustment as couples, though reunited physically, may not have yet reconnected emotionally.

Similarly, within the cycle of violence and abuse, the abuser may enter a “honeymoon” phase after a crisis, expressing remorse and seeking reconciliation. It’s a time of vulnerability and hope, where the promise of change lingers in the air.

Yet, as in the emotional cycle of deployment, this hope can be fragile and easily shattered when the cycle restarts. What’s striking is the normalization of the honeymoon phase in both scenarios.

The Normalization of the Honeymoon Phase

In the emotional cycle of deployment, it’s seen as a natural part of the reintegration process, where couples may need time to reconnect emotionally.

However, in the cycle of violence and abuse, this same phase is often brushed aside or accepted as a temporary respite from abuse, all under the banner of supporting the service member and serving our country.

This parallel serves as a stark realization of how certain behaviors and patterns have been normalized within military families.

It’s time to question these norms and prioritize the well-being of both caregivers and service members.

Current Strategies and Their Shortcomings

Addressing the cycle of violence and abuse is similar to navigating a minefield, with potential emotional explosions at every turn. Present strategies, often rooted in domestic violence stereotypes, fail to address the nuances of military caregiving.

I’ve experienced this isolation firsthand. The feeling of loneliness doesn’t stem from a lack of community love or care but from inadequate resources and support systems.

A pervasive stigma surrounds domestic violence in military families, acting as an invisible shackle. This stigma muzzles us, deterring us from seeking help or sharing our stories.

We’re made to feel that acknowledging domestic abuse is a betrayal. It’s a heavy burden to bear, concealing the pain behind closed doors.

The Invisible Wounds of Caregiving

While addressing the cycle of abuse is vital, it’s also essential to recognize that these challenges can contribute to emotional strain and even mental health issues. In my previous article, “Invisible Wounds of Suicide Prevention,” I dove into the invisible wounds of suicide prevention and the importance of accessible resources for caregivers and service members alike.

However, silence benefits no one. It strengthens the cycle, making healing even more elusive for our loved ones. It’s imperative to break free, recognize our challenges, and chart a path that genuinely supports caregivers and service members.

Finally, we will explore the need for a more comprehensive toolkit for military families, one that includes education and resources to navigate these complex challenges.

Seeking a Path Forward

Confronting the Cycle of Abuse

The cycle of abuse within military caregiving, though challenging, must be addressed to foster an environment where support and understanding prevail over silence and stigma.

Recognizing and understanding this cycle is crucial for initiating meaningful change.

Broadening the Responsibility

The onus of addressing these issues doesn’t lie solely with caregivers. Researchers, policymakers, and veteran support organizations must also play a role in recognizing and addressing domestic violence within military caregiving. This issue needs systematic attention and action.

Empowering Individual Caregivers

- Education and Awareness: For new military spouses and caregivers, it’s vital to be informed about the potential challenges, including the risk of abuse. Understanding these risks is a key part of your journey.

- Transitioning from Active Duty to Civilian Life: Recognize that strategies and behaviors effective in active duty may require adaptation post-service. This transition involves developing new coping mechanisms and support systems.

- Personal Strength and Seeking Help: It’s important to know that experiencing abuse is not your fault. Reach out for support when needed, and prioritize your mental and emotional well-being. There’s strength in asking for help.

Engaging Local Communities

- Open Dialogues: Encourage conversations within your community about these challenges. Breaking the silence around abuse is essential for healing and support.

- Sharing Stories: Share your experiences. Personal narratives of struggles, resilience, and breakthroughs can guide and inspire others.

A Call to Action: Building a Better Future in Military Caregiving

As we navigate the complexities of military caregiving, it becomes evident that we need more than just personal narratives and anecdotes. We need a concerted effort from researchers, policymakers, and organizations to understand, address, and ultimately prevent the cycle of violence and abuse within military families.

For Researchers:

- Conduct in-depth studies on abuse within military caregiving, focusing on the effects of military culture, deployments, and transitions to civilian life.

- Your findings are crucial in identifying effective interventions and prevention strategies.

For Policymakers:

- Recognize the emotional aspects of military caregiving.

- Create policies that support the mental health of caregivers.

- Allocate resources for families impacted by violence and abuse.

- Develop training programs tailored to the unique stressors of military families.

For Veteran Service Organizations, Nonprofits, and Government Agencies:

- Make this issue a part of your agenda.

- Work alongside researchers and policymakers to develop empowering programs for military families.

- Integrate caregiver experiences into your support systems.

- Strive to ensure that no military caregiver faces their challenges in isolation.

In closing, these words stand as a beacon, guiding us towards a future where military caregivers are fully supported and understood. It’s a unified call for action, urging us to blend personal experience with systemic solutions. As we move forward, let’s embrace this opportunity to transform military caregiving, ensuring a future where compassion, support, and understanding triumph over silence and adversity.

Together, we have the strength to create lasting change, making a positive impact on the lives of military families.